Glazes

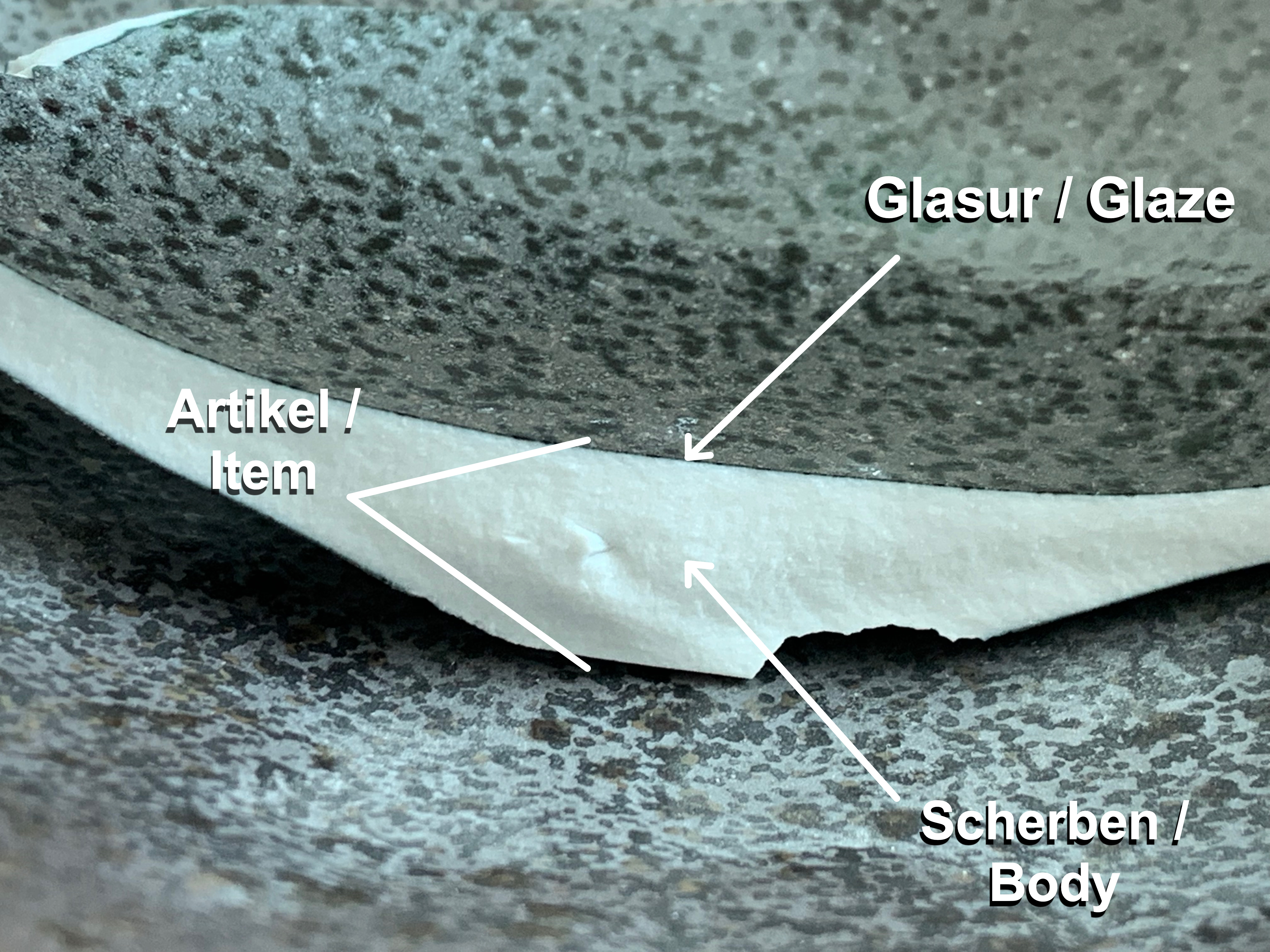

Undecorated porcelain - like almost all other ceramic qualities - usually consists of two components (layers): the fired body (the body) and a glaze that encloses it. In the case of decorated ware, up to two further layers are added, the actual decorative image and often also a flow, which protects the decoration like the glaze protects the body. This section, however, will refer purely to the glaze and its interaction with the various types of ceramic ware.

As the surface of a piece of tableware, the glaze - and thus its quality and finish - has special properties in relation to the usability of a piece of tableware. It is therefore important for the specialist to know the properties and differences of a glaze, at least in its rough outline.

Types of glazes for ceramic tableware

Below we list the most common types of glaze for ceramic crockery in ascending order of their ceramic quality class.

| Name of the glaze | mostly used for |

| Clay glaze | pottery |

| Frit glaze | Vitreous China |

| Frit glaze | Fire pottery |

| Salt glaze | Earthenware, Stoneware |

| Lead glaze | Earthenware, Majolica |

| Tin glaze | Faience |

| Feldspar glaze porcelain | Porcelain, dental-ceramics |

| Corundum glaze | Cutting & grinding ware |

What is a ceramic glaze?

The glaze is used to finish the surface of most ceramic products and, in contrast to the crystalline porous base material, is a glass-like closed surface layer. The composition of the glaze is similar to that of classical glass. The composition, quality, degree of mixing, grain size and preparation of glazes cannot be used arbitrarily.

The glaze is a thin, glassy, dense coating on ceramic products. In the case of white porcelain, it is usually more transparent and colorless, but in the case of colored tableware, it may also be colored. This not only gives a glazed ceramic object a shiny appearance, but usually makes it impermeable to liquids and gases. Glazes are light-bodied, silicate glass types of varying composition.

Depending on the grain size of the starting materials and the crystalline phase formed during firing, a ceramic product has a certain surface roughness which favors contamination. By applying a glaze, the surface is smoothed and, if necessary, also embellished in terms of color. Above all, however, the glaze decisively improves many application-relevant properties of the ceramic product (e.g. electrical behavior, mechanical strength, chemical resistance and the like). The glaze is richer in flux than the fired ceramic body. At high firing temperatures, it therefore has a solvent effect on the body.

When to apply glaze on the dishes?

Generally speaking, it can be stated that the glaze is applied to the "glaze-ready body". Already this stage of a ceramic object documents the difference in the later further processing and usability of the final product. The consequence of a ceramic glaze is the formation of an intermediate layer, which leads to a firm interlocking of the glaze with the underlying body in the finished product. By adding color bodies (metal oxides), a wide variety of glaze colors can be achieved and colored glazes can be produced.

For the strength-increasing effect, the glaze must be very precisely matched to the thermal expansion coefficient of the body. Slight compressive stresses in the glaze increase the strength of the finished product, tensile stresses lower it and are therefore undesirable. So-called engobes - thin-bodied clay mineral masses - are applied as mineral coatings to ceramic surfaces by dipping, rolling, spraying or brushing. Unlike glazes, engobes are porous and largely free of glass phase. They usually consist of refractory oxides (Al2O3, SiO2, MgO, ZrO2), mixtures thereof or refractory minerals such as mullite, spinel, zircon silicate, but also kaolin or clay.

Glaze condition in single firing

In the section /knowledge/kiln-and-firing/gas-phase/ we describe the important phase of porcelain firing in which organic constituents and embedded carbon particles are burned out of the ceramic body. The length and intensity of such a "cleaning phase" also depends on the purity of the raw materials. As a rule of thumb, the purer and higher the quality of the raw materials, the lower the intensity of such a gas phase.

Due to very pure raw materials, many Asian manufacturers are able to carry out the gas phase in the same firing process as the hard firing. Such a mono-firing is energetically considerably superior to the double-firing process and is one reason why many tableware items manufactured in Asia can be produced more cheaply than European ceramics and porcelain.

If a manufacturer masters the mono-firing process, then the time of glaze strength is the so-called green body, i.e. the air-dried body brought into shape. As far as the ability of such air drying is concerned, the Asian factories also have a considerable advantage over the European ones, which can use their natural ambient temperatures for drying, whereas in Europe one has to use heated drying chambers. In many cases, however, modern kiln plants in Europe now use so-called heat recovery systems for pre-drying the green bodies. In Asia, with 7 to 10 months of sun and high temperatures, this is not necessary.

Glaze condition in double firing

The majority of European porcelain is produced using the dual-firing method. It goes without saying that these manufacturers like to justify their more expensive production method with "better" and "higher quality". But whether it is really "better" is not the point here. In the dual firing, the green body is compressed into a biscuit-like state in a pre-firing between 800 and 950 °C. This is why this firing method is also known as dual firing. This is why this firing is also called biscuit firing. During this pre-firing, a considerable dehydration process already occurs and significantly reduces the porosity. The following rule of thumb applies: The higher and longer the biscuit firing, the denser is the body.

1:0 for single firing

The most important finding and distinction for the glaze strength of a ceramic body is based on the indisputable, physical property that a porous body can basically absorb more liquid and store more moisture than a dense body. Thus, a well-dried green body usually absorbs more glaze liquid than a ceramic product produced by dual firing. The glaze liquid can sink deeper into the body and thus forms a larger contact surface between glaze and body. As a result, the glazes of monofired tableware are often thicker and more resistant in comparison to those of the dual-firing process.

How is a glaze applied?

In the production of ceramic tableware, the bodies ready for glazing are usually dipped. This is done by hand in traditional production to this day and is the fastest, easiest and cheapest glazing method. To the layman, hand glazing may seem primitive, but it serves the same purpose as highly industrialized glaze lines. Each glaze method in itself has many advantages and disadvantages. Small batches and individual glaze colors can be produced much more cheaply and efficiently in hand glazing than on glaze lines. In contrast, of course, industrial robots can be more precisely adjusted and run 24/7 without a break. To illustrate the different types of glaze, we have put together a short video for you.

The importance of a glaze for the private user

The private consumer judges the quality and finish of the piece of tableware primarily by the glaze. That is why retailers like to call the glaze the "outer garment" of the porcelain. However, this is done in ignorance, because the very fact that porcelain consists of several components is not known to most people. Pinholes in a glaze are often judged by the layman as "bad glaze", although the cause is often to be found in the exhaust residues of the fuels and has absolutely nothing to do with the glaze.

Even the classic iron spot is not caused by a bad glaze, but mostly by the burning out of microscopic, metallic residues in the body.

The importance of a glaze for the professional user

Especially for the glazes of hotel porcelain and catering tableware, our definition of true quality of a utility article is particularly true: The true quality of porcelain does not consist in a hand-sorted selection of tableware pieces of perfectly flawless surfaces, but in the unique functional and utility properties that result only from the combination of kaolin, quartz and feldspar from a temperature above 1,320°C.

If you think that real professional porcelain is measured by appearance and appearance, you are very wrong!

The glaze decides the sensitivity in commercial use. The glaze ensures the surface hardness and ensures the cutting- and scratching resistance of a dish. As you can see in the upper table, the feldspar glaze of the genuine hard porcelain is second in the ceramic doctrine. This means that the glazes of genuine porcelain are generally harder than those of all other ceramic grades such as Earthenware, Vitreous China, Durable Tableware.

In the family of kitchen and tableware, only in the case of genuine porcelain there is a fusion and vitrification of glaze and body above a temperature of 1,320 °C. Only with porcelain is the coefficient of expansion of glaze and body identical and thus protects against crackle cracks, glaze breakage and also edge impact. Thus, porcelain glazes ensure higher hygienic stability than glazes on ceramic tableware.

Only feldspar glazes of porcelain with their high quartz content and low viscosity harden after fusion and vitrification to form an amorphous, dense protective shield, which is resistant to bases, alkalis, acids, germs, fungi, spores and viruses. Therefore, porcelain glazes are also extremely resistant to corrosion by chemical detergents.

True feldspar glazes are free of heavy metals such as lead, cadmium and cobalt. Unlike many lower-quality ceramic dishes, no harmful substances can dissolve out of the porcelain glazes and transfer to the food, posing a health hazard. More on this in a report by the Bundesanstalt für Risikobewertung.