Type of manufacture

Factory or manufactory ware - these terms are used very differently, especially in the case of porcelain, and are usually in stark contradiction to the correct definition. If you look up the term "manufactory" on Wikipedia, you will find other distinctions than those currently widely used in the German language. We explain the differences from our point of view.

The image of a manufactory from Wikipedia

"... A manufactory (from Latin manus "hand", and facere "to build, to do, to make, to manufacture") is a production site of craftsmen of different professions or highly specialised sub-workers of a craft, whose different work processes aim at the production of a common end product. In European economic history, they replaced the medieval crafts and were themselves displaced by factories in the course of industrialisation. Manufactories differ from the latter in that they are less mechanised and work is predominantly done by hand, although the boundaries between the terms can be blurred. Manufactories arose in Europe primarily in the early modern period, both from private and state initiative...."

(Picture: Traditional casting of hollowware 2004, left: Knud Holst)

The image of a manufactory of the Porcelain

Until the late 1980s, porcelain dishes and exhibits were made almost entirely by hand. On our page "Jobs in production" we have listed the 41 most important crafts in porcelain production. As late as 1979, the Federal Association of the Ceramic Industry in Selb published an insert on ware for its member companies:

"... A hundred hands are needed to make a piece of porcelain. Porcelain is fired several times in a fire with a temperature of more than 1400 degrees. The raw materials are stone and earth. But hands are not machines - and from hands, fire and earth can never emerge completely identical creations...."

(Image: Highest Porcelain Manufactory, production of the Hessian Lion 2018)

However, the majority of porcelain manufacturers did not call themselves a manufactory. Even Rosenthal Porzellan, Waldendorfer, Hutschenreuther or Arzberg never chose this designation in their heyday, leaving the term "manufactory" to the artistic workshops such as Goebel Porzellan, Meissen Porzellan, Hoechster Porzellan, Augarten, Herend, KPM and other royally subsidised noble brands. Whether this was due to respect for these fine porcelain makers or to the desire to produce "affordable and good porcelain" for consumers is a matter of conjecture.

Holst Porcelain/Germany Factory or Manufactory?

Neither! We describe the manufacturing method of our goods on each of our articles as "traditional" or "industrial", as a derivation "factory" or "manufactory" cannot be derived from our point of view. Even a high-tech factory such as Kahla Porzellan still has some products that can only be made by hand, i.e. "a la Manufaktur" (according to Wikipedia).

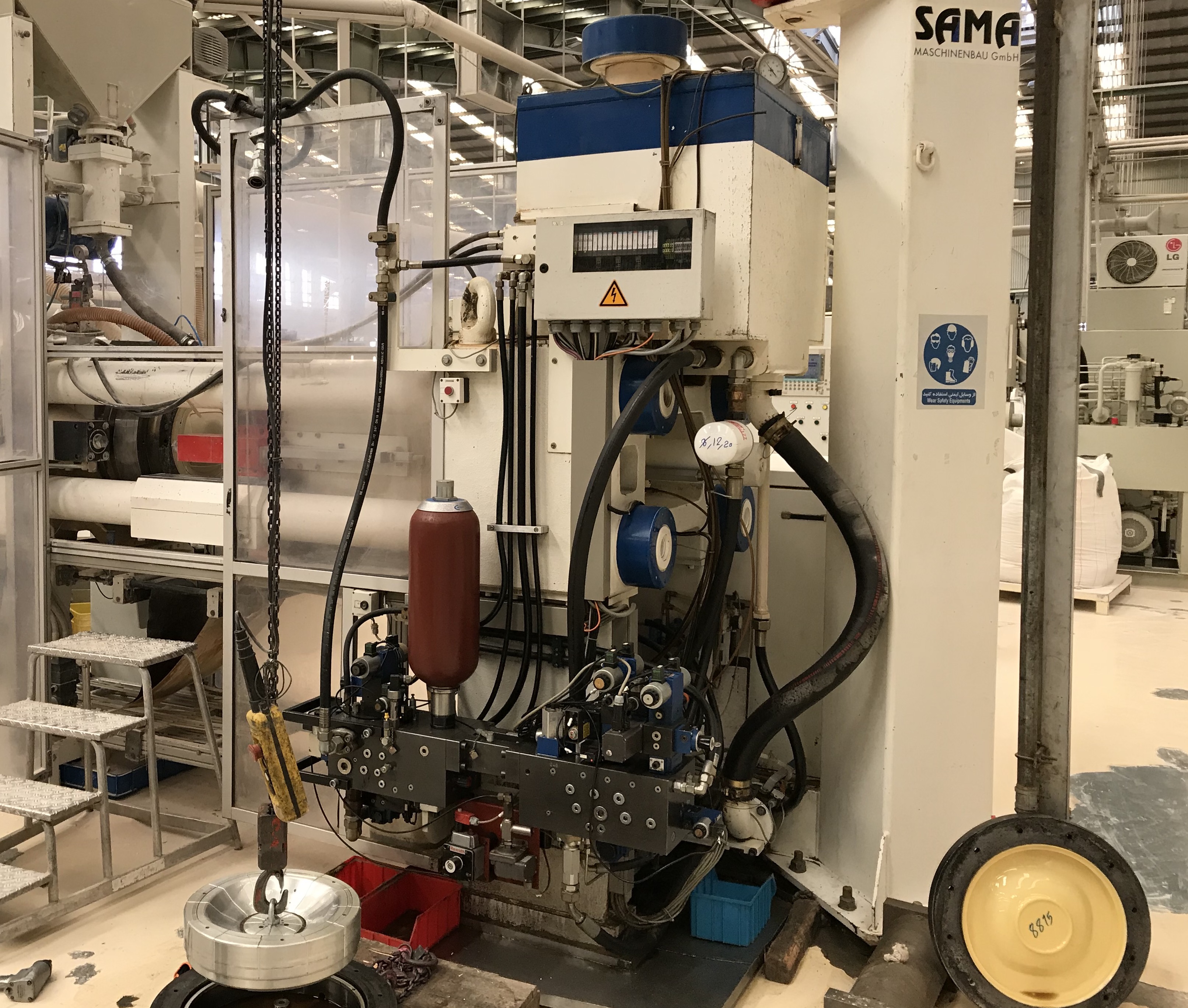

(Image: Industrial production of porcelain plates)

Apart from that, we also consider ourselves porcelain makers and leave the designation "manufactory" to the circle of manufacturers who receive ten to thirty times the price for their so-called "works of art" than our porcelain tableware for the "normal person". We consider it more honest to advertise our products with a decided distinction between traditional and industrial production methods.

The Great Sorrow of Manufactured Porcelain

Manufactured goods are a bit like a beehive: everyone appreciates their work, but no one wants it! The handiwork of a high-quality manufactory piece is responsible for the artistic difference between one piece and another. But differences in tableware pieces, especially in shape, colour, diameter or even height, are not at all liked by the consumer. Plates in a stack should preferably form a tower aligned with the perpendicular, handles and snouts the same size, the same length and completely the same shape.

(Picture: Isostatically - industrially pressed flat parts)

In other words, although the majority of consumers appreciate the term "manufactory" as a high-quality (and usually more expensive) designation of origin, they perceive the natural, handcrafted differences in the goods as poor quality. As a manufacturer of sophisticated utility porcelain, we therefore define the quality of porcelain in this way:

The true quality of porcelain does not consist in a hand-sorted selection

of pieces of crockery with perfectly flawless surfaces,

but in its unique functional and utility properties,

which only results from the combination of kaolin, quartz and feldspar from a temperature above 1.320 °C.

Only in this way can the needle mullite form from these minerals,

which gives porcelain its unique properties.