Johann F. Böttger

On the image page of the Association of the Ceramic Industry (logo above) you will unfortunately also find a repetition of this misrepresentation of the invention and origin of white gold. 300 years of German porcelain is a proud achievement and certainly documents a participation of German brands in the development of porcelain. But those who complain that Chinese porcelain factories copy German porcelain are unfortunately adorning themselves with borrowed plumes! In English, porcelain is called "Chinaware", and this name is self-explanatory.

The "German invention of porcelain" must have meant "Germanisation" or "Einindeutschung", because in Western Europe at the beginning of the 17th century it was not possible to imitate Chinese pieces for lack of raw materials and firing techniques. Explorers, such as Marco Polo, are often mentioned as historical exporters of white gold. Almost none of the historians, however, elaborate on the definition of "white gold". One could imagine that world travellers not only brought back the porcelain itself, but that precious objects from China were brought to local princes as a status of unimaginable power and wealth. Embedded in the legendary tales of its bearers, porcelain soon became a symbol of rank and significance for its owners. The passion for collecting and the insatiable lust for representation and power of the Elector of Saxony then allowed porcelain to mature in Europe.

The Origin of European porcelain

Johann Friedrich Böttger, German alchemist, *04.02.1682 Schleiz, †13.03.1719 Dresden, succeeded in producing Böttger stoneware in Dresden in 1707, which bears his name, and European hard porcelain in 1708 with E. W. von Tschirnhaus. Böttger was head of the Meissen porcelain manufactory until his death. The so-called Böttger porcelain produced there in Böttger's time - from around 1715 - are mostly copies of Chinese porcelain with Baroque decorative shapes.

Celebrated as the "inventor of porcelain", Böttger stood between a child prodigy and an impostor when it came to the consideration of royalty. In 1701, Böttger turned a silver coin into a gold coin in the eyes of Berliners, making a name for himself for the first time. While Johann Friedrich Böttger was persecuted to be hanged for his heresy, the impostor found refuge in the Saxon city of Dresden under the protection of August the Strong to further develop his alchemical skills. In 1705, the gold laboratories were moved to Meissen to protect the developments from the events of the war.

Although Böttger may have seen "his neck already in a noose", he was persuaded by his colleague Ehrenfried Walter von Tschirnhaus to participate in the development of porcelain. August the Strong paid for everything that put him above his opponent Peter I, the Tsar of Russia, in terms of expressiveness and representation. In 1706, Tschirnhaus succeeded in producing the first red-fired bricks of a solid consistency. Some historians use this story about the juggler Böttger as an explanation for the term "white gold". Ultimately, both circumstances may have contributed to this definition, although we do not know for sure.

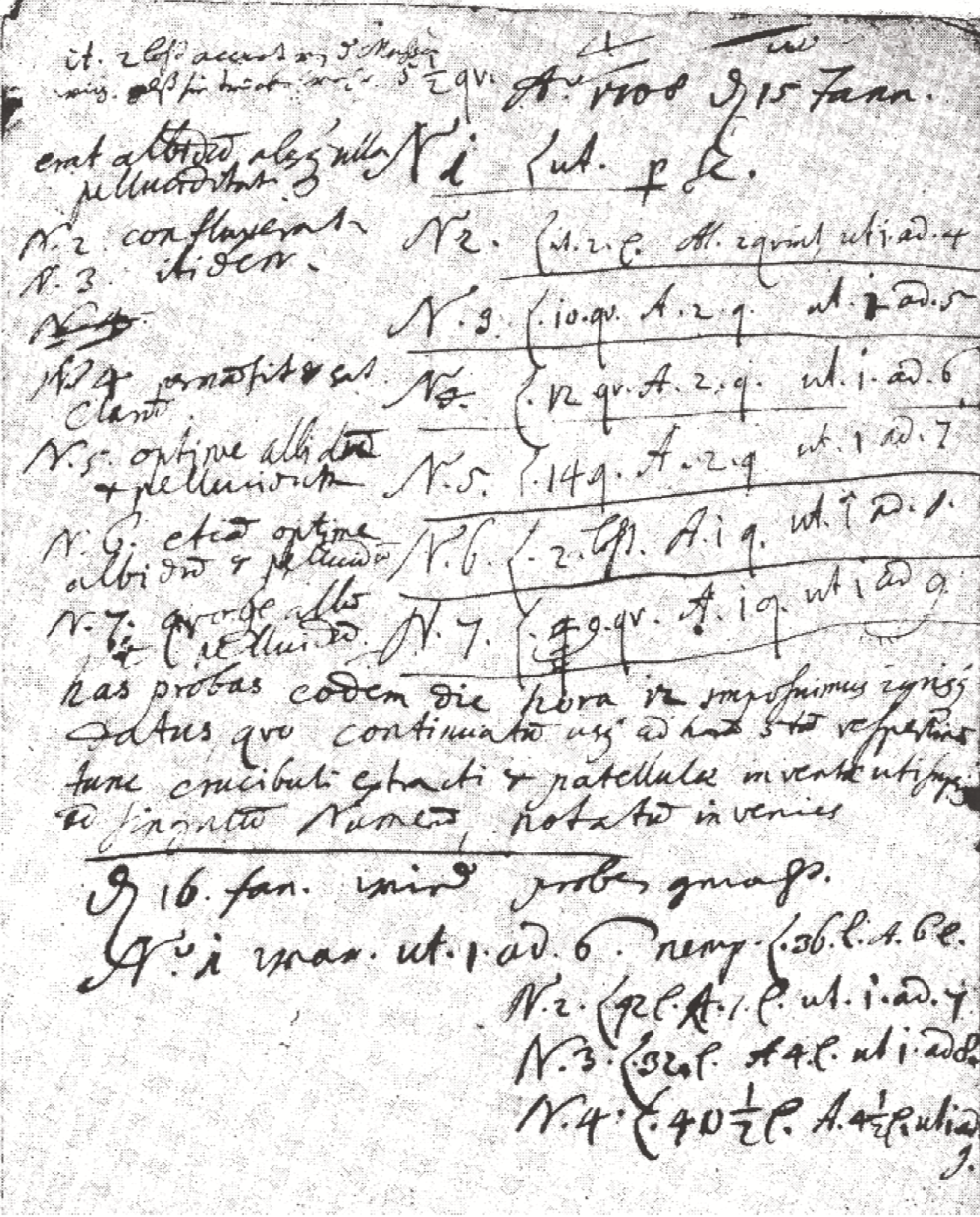

In the graphic above you can see the original note of Böttger's series of experiments with various components for porcelain production. This proves that the invention of porcelain was no accident, but the result of a series of purposeful experiments. This note of 15 January 1708 is, so to speak, the "birth certificate" of European hard porcelain, while the actual birthday of hard porcelain is 28 March 1709, as Böttger reported on the successful experiments carried out on that day in the Saxon court chancellery. Meissen porcelain was therefore invented in Dresden.